|

|

|

|

|

«

Previous Thread

|

Next Thread

»

|

|

| About Us | |

| We are a community-driven platform of critical code experts and researchers working on the Middle East. The goal is to promote procedural and digital literacy by providing a research & development platform for innovative knowledge production on the Middle East. We believe that procedural literacy provides a key to 21st century democratic practices. | |

|

| ARCHIVE |

|

|

| R-Shief Blog |

| R-Shief’s new blog on various issues concerning transnational Arab culture, media, technology, critical code, or other interdisciplinary research questions. |

| Navigation: |

| #1 | |

|

Administrator

29-08-11 |

Eighteen Hours to Thirty Six Hours Entering #Tripoli

On August 20, 2011, R-Shief’s real-time Twitter mining revealed patterns and similarities in the visualization of the events in Zawiya and Tripoli. As journalists, activists, and scholars struggle to understand the last eight months of unprecedented mass mobilization and political upheaval in the Arab world, R-Shief is carving a unique and critical space in storing, processing, and analyzing information. Using its real-time analytic tools last weekend on its extensive repository of content from social media and other websites on the so-called “Arab Spring,” R-Shief Labs (henceforth Lab) produced timely, empirical analysis about the rebels’ military launch on Tripoli. And the accuracies in the conclusions prove to be quite interesting.

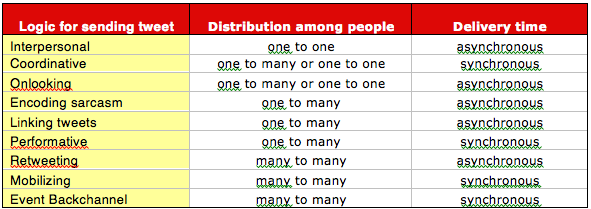

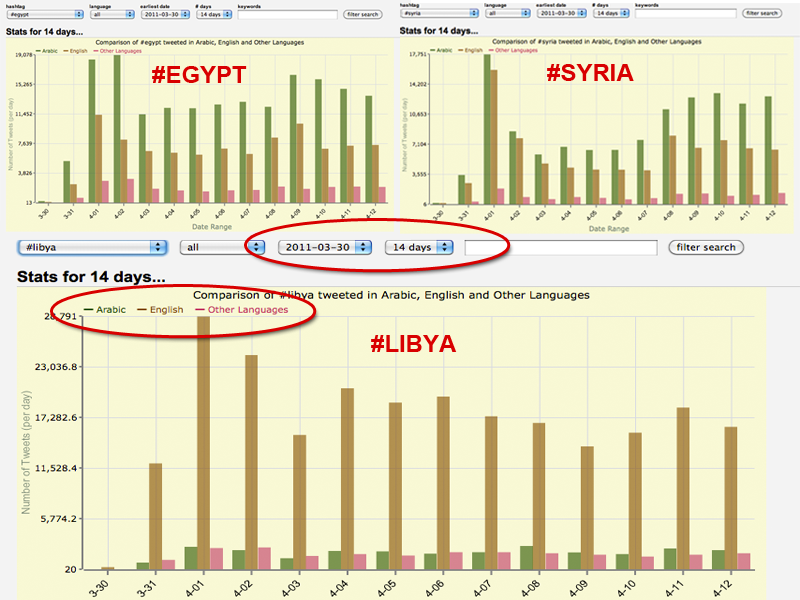

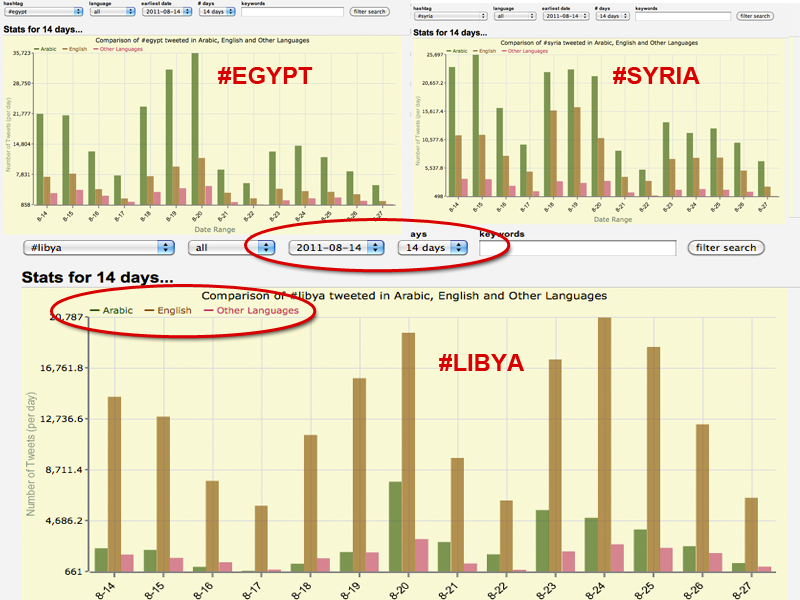

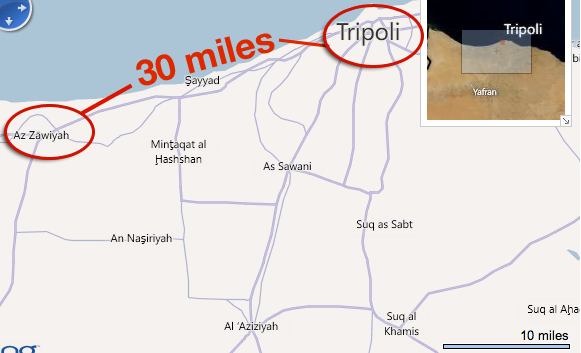

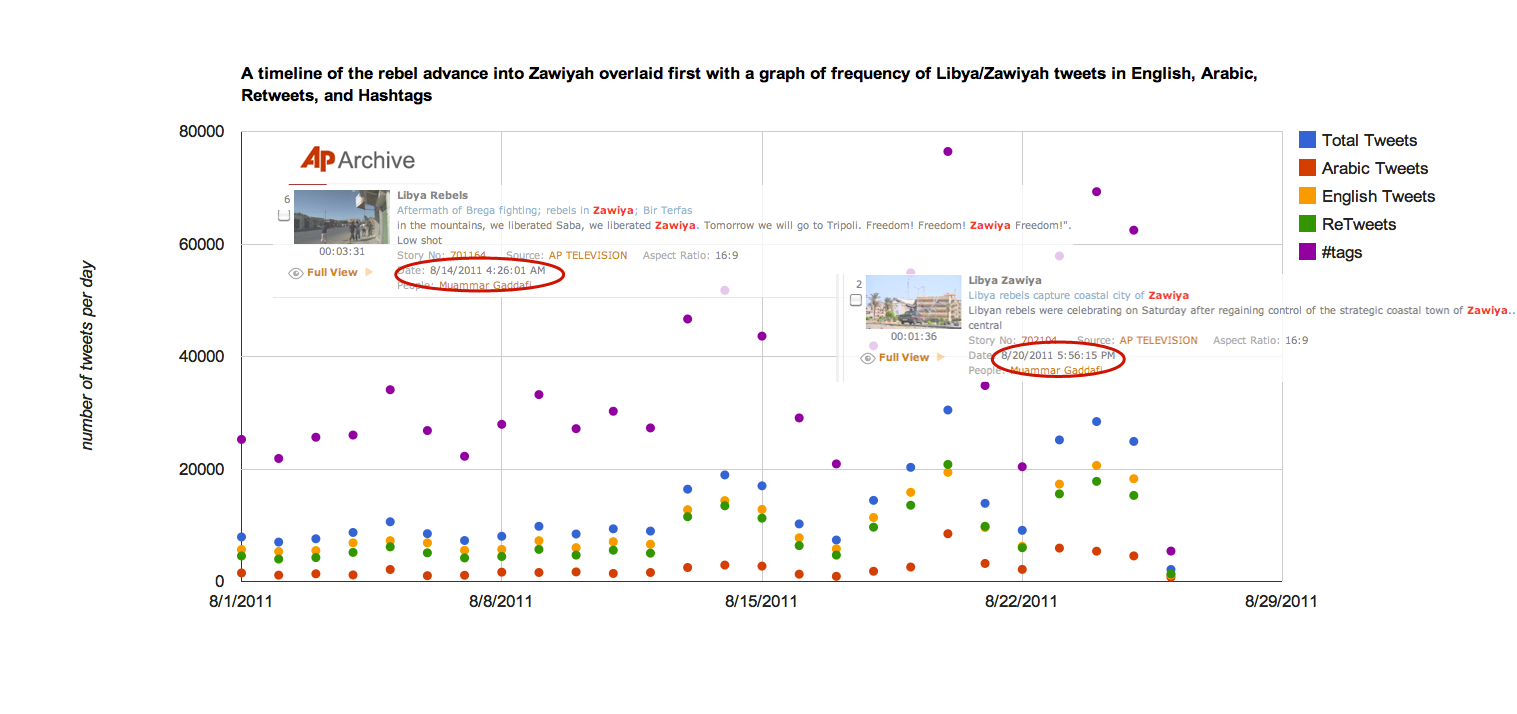

After months of rebel forces’ gains and losses across Libya’s territory, and the initial liberation of Benghazi with the help of NATO, it took the rebel forces only eighteen hours to finally take control of Tripoli's city center. On the one hand, it seemed a rapid turn of events. On the other hand, the rebels experienced major setbacks and committed errors of judgment. The setbacks included temporary loss of territory that they thought they had liberated; the error in judgment, or perhaps in the discipline of the forces and security control that they demonstrated, came with the announcement of the arrest and detainment of Seif al-Islam Qaddafi, the Libyan dictator’s son and putative heir. A short time later, he appeared on television to prove that if the rebels had captured him, he easily escaped and if they had not captured him, then they had made a public relations blunder. For months, NATO has been bombing key targets aimed to halt the abilities of Qaddafi’s military and his loyalists while the rebels barely made progress. It seems as if something changed radically allowing the rebels to make great strides, including taking the city of Tripoli, neighborhood by neighborhood. The announcement of the rebels taking control of Tripoli came fairly quickly, especially when one considers the many months that it took both the rebels and NATO to get to that point, processes that also including the beginnings of political recognition for the rebels’ government, the Transitional National Council (TNC). Placed on a larger time spectrum, Qaddafi held power for more than four decades in Libya but the actions that led to his marginalization took less than one year. It is as if Libyans’ fears diminished as they banded together and experienced rebel accomplishments. The power of political possibility demonstrated is incredible. A recent conversation with Liz Losh, professor at UC San Diego and author of VirtualPolitik, about R-Shief’s findings led to a useful reminder about the existing limitations of expression with regard to the “economics of social media.” Indeed, there are no definitive economic models to study the value of our associations, our temporality, or how to quantify things in the present.1 This absence cries out for examining emerging trends on large-scale datasets of social media. R-Shief’s mining and compilation of data aims to fill that gap by working among networked communities as a trustworthy commentator, a reliable source. As this article analyzes data mined from Twitter, examining its impact on Libya, Egypt, Oslo, or other global issues, a basic literacy about the nature of tweets is essential. Indeed, one of the goals of the Lab is to help non-experts be able to re-imagine their relationship to technology and gain a deeper understanding of the implications of using or choosing not to use technology. Social media and Twitter in particular have played a leading role in spreading and fomenting social uprisings, such as those witnessed in Egypt and Tunisia. It has quickly spread breaking news – in advance of news organizations – as demonstrated in the killing of Osama bin Laden. R-Shief’s recent analysis of tweets from Libya illustrates another facet of insight gleaned from social media: how certain everyday words can suddenly reflect a rising momentum of a rebel advance, or a global act of all kinds of media watching. In this article, I will explain how by using R-Shief’s tools to generate dynamic, interactive graphs within hours of events in Libya, one could see that it took basically twenty-four hours for the rebels to take over Zawiya – roughly from when the fighting began to when they captured the main square. Just as I had seen the words “now” and “began” appear in the word clouds generated from frequency counts from Thursday night tweets on Zawiya, I began to see those words appear in tweets on Tripoli. SOME GROUNDWORK BEFORE THE ANALYSIS Emerging from the fields of design research and performance art, R-Shief’s tools and methods are centered on a practice of “radical presentness.” Rather than approaching human behavior, and therefore, art, as mimetic2, R-Shief is conceived of through an understanding of human behavior as in a state of “becoming.” From this perspective, art does not imitate life, but rather, it takes on a double identity. This collapse of context can be understood theoretically, through the works of Deleuze and Guattari, specifically in their chapter on “Becoming-Intense, Becoming-Animal…” in A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, and among many other philosophers and artists, who have written on the nature of human experience and the telling of it as something that never quite begins, nor quite ends, but is in a constant state of becoming. In this case, R-Shief is designed to embody this in its code and machine intelligence. For example, in one line of code (represented in a “cron job”) the request to data mine Twitter, Facebook, blog, forum and website content is executed every two minutes. For purposes of doing comprehensive research and publication using R-Shief’s repository and analytic tools, the Lab has begun to build a taxonomy to explain both the nature of tweets and R-Shief’s dynamic database of tweets. The table below represents the communication logic of a tweet – its purpose, and how it happens. Each type of tweet – onlooking, coordinative, retweeting – behaves slightly differently. In the table below we have mapped out two behavior patterns – one, a tweets’ distribution among people, and two, the delivery time between when the tweet is sent and when it is received. Another way to explain how this works, from a design research approach, – is that Twitter is a space designed for others to create in. In order to understand that new world called Twitter, we must understand the rules of that world – even if temporality, erasability, and mutability are among those rules. This tweet taxonomy is designed to remain in development as data scientists and others provide us with even more insightful research on the meaning of Twitter.  Fig. 1 Taxonomy of communicative logics of tweets In the case of #Libya tweets, since the very beginning, it is more likely that majority of people who are tweeting about #Libya are not in Libya. The clearest indication of that assumption, even before NATO’s interference, is that tweets in Arabic were coming in around 2,500 a day while tweets in English were coming in 20,000 a day. This is remarkable, especially when you compare them with tweets on #Egypt or #Syria in the graphs comparing two different below.  Fig. 2 R-Shief’s Twitterminer compares number of tweets of in Arabic (green) to tweets in English (brown) on #Libya with tweets on #Egypt and #Syria during the first two weeks in April 2011 when NATO took control of all military operations for Libya under United Nations Security Council Resolutions 1970 & 1973 on March 31, 2011. The graphs above did not fluctuate much since then (see Fig. 3). There has been a slight increase in Arabic tweets, but nothing indicative of a local population. It certainly seems that the people tweeting on #Libya are different from those tweeting on #Syria or #Egypt, where the phones and tweets are an integral part of organizing the rebellion. In many YouTube videos and images seen, Libyan rebels appear to carry AK47s rather than the cell phones of Egyptian regime opponents. One possible reading from this comparative analysis is that the people tweeting on #Libya are communicating a “voyeuristic” logic and perhaps “encoding sarcasm” and “linking media.” They are, thus, most likely not Libyans on the ground in Libya.  Fig. 3 R-Shief’s Twitterminer compares number of tweets of in Arabic (green) to tweets in English (brown) on #Libya with tweets on #Egypt and #Syria when rebels advance in Zawiya for over last two weeks in August 2011. Some analysis of the population sample is required to gain a deeper understanding of who is tweeting and how that contributes to the spread of information. Ultimately, R-Shief relies on Twitter’s public API (not Twitter’s private, $32,000/month pipe called the “gnip”) for its main source; since we cannot know how much of a sample the public API is out of the complete corpus from Twitter, the analyst detects a limitation in the data, much like a box or a series of boxes being missing from a historical archive. That being said, most researchers conduct analysis of tweets only using Twitter’s API because of the costly nature of the full pipe, though it is not always made explicit. Twitter also imposes a restriction: it has set a download limit of 1,500 tweets for each pull, and users can only access up to the previous 7 days of tweets. This is a critical point. In order to do any in-depth analysis of tweets, one needs a history of the population sample. By providing an archive of tweets going back as far as 2010, R-Shief offers the research community a tremendous resource. R-Shief’s system is designed to automatically pull up to the maximum allotted tweets every 2 minutes and save them onto its cloud computing network. For over a year, this unique data mining design far surpasses the mining of over 175 Twitter feeds every 2 minutes, making R-Shief’s archive of Twitter’s public API one of the most extensive and thorough repository of tweets on the Middle East publicly available. As for the tweet itself, it is comprised of 140 alpha-numeric characters, produced by an individual using either a text enabled phone or a computer. And these tweets can be organized by hashtag (a sort of “channel”) by adding a “#” in front of a group of characters (usually, a word). This is done in order for meta-data, such as geo-tagging, to be embedded in the stream of tweets identifying tweeters’ chosen identifier when they make their postings. Accurate geo-location is rare as very few users allow for geo-tagging, which requires user permission. There is a popular assumption, however, that when people are tweeting, they are tweeting what is happening in the moment around them in real time and space. R-Shief Labs has built a swarm computing system, Twitternommer, which basically runs Twitterminer and enables researchers to filter and export data on the command line. It is a type of machine learning of various languages used in Twitter. As of now, Twitternommer is building a lexicon of Twitter in Arabic, English, French, Spanish, German, and Farsi character by character. It also parses out the retweets, other hashtags, and users mentioned in the tweets. It removes all extraneous characters (such as html tags, links, and headers) and creates a semantic word cloud analysis. This data can be analyzed by the hour and by the minutes. Twitternomer provides real-time analysis of R-Shief’s entire repository. CASE STUDY: COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF #LIBYA TWEETS ON ZAWIYA AND TRIPOLI Friday, 8/19/2011 7:55pm Los Angeles time/ 4:55am Zawiya time: R-Shief received an SMS that the rebels had won over Zawiya, a key city near the Mediterranean coast in Libya only 30 miles west of the capital, Tripoli. This message signaled to R-Shief Labs to start analyzing its data to see if online information could add insight into the unprecedented events in Libya. The analysis conducted over the next couple days on tweets about #Libya illustrates another facet of insight gleaned from social media: how certain everyday words on a social media platform suddenly seem to reflect the rising momentum of a rebel advance.  Fig 4. Map of northwestern coastline of Libya from National Geographic. Saturday, 8/20/2011 2:00pm Los Angeles time/ 11:00pm Zawiya time: The first step in the process of analyzing what was happening in Libya through real-time social media was to export a history of R-Shief’s tweets on #Libya from March 30, 2011 through the present. The graphs reveal interesting patterns and disruptions to the baseline data of R-Shief’s database on #Libya from March 30, 2011. The number of tweets per day grew to similar activity levels as early on in the mass mobilization efforts in Libya in the spring. And, even more noticeably, the number of channels, or hashtags, increased exponentially over the last ten days in August 2011. Fig 5. Interactive graph of daily frequency of #Libya tweets: March 30, 2011 - August 25, 2011 Saturday, 8/20/2011 4:20pm Los Angeles Time/ 1:20am (next day, Sunday) Tripoli time: A few hours later same day, Saturday, the rebels had advanced to Tripoli and the fight for the nation’s capital. To compare the tweets on Tripoli with those on Zawiya within the #Libya corpus of data, I first conducted keyword search to filter out Zawiya and Tripoli tweets from the same population sample.  Fig 6. A timeline of the rebel advance into Zawiya overlaid with graph of frequency of Libya/Zawiya tweets in English and Arabic, as well as Retweets and Hashtags. Fig 7. Interactive graph includes a timeline with a play button at the bottom, and three different tabs at the top. If you hover over the word clouds, they will change when timeline is played. In this dynamic, interactive graph, I was able to see that it took basically twenty-four hours for the rebels to take over Zawiya – roughly from when the fighting began to when they captured the main square. See the steep peak with the orange, word cloud circle at the top. Just as I had seen the words “now” and “began” appear in the word clouds generated from frequency counts from Thursday night tweets on Zawiya, I had begun to see those words appear in tweets on Tripoli. It took forty minutes to process gigabytes of tweets data, visualize and analyze it. And so R-Shief sent out a text message to its mobile subscribers: “Doing analysis on R-Shief’s tweets – prediction is Tripoli will fall in next 18-36 hours! And [potentially] will affect Syria and Yemen.”  Fig 8. Word count of most frequent words tweeted on #Qaddafi from 8/18/2011-8/22/2011. Sunday, 8/21/2011 5:00pm Los Angeles Time/ 2:00am (next day, Sunday) Tripoli time: And indeed, eighteen hours later, Al Jazeera, Facebook, and Twitter were broadcasting that Mohammed Qaddafi (eldest son) surrendered; Seif Islam had been captured (but later on Monday, there were claims he was checking into a hotel); and that al-Senussi, the head of intelligence, had been assassinated. Days later, the fighting in Tripoli continues, however, clearly things are changing.  THE FUTURE: R-SHIEF AND ITS DYNAMIC ROLES Oriented in this unique approach, R-Shief is able to harness the liminal space between groups of people trying to deal with archival material and digital repositories on the Middle East. Some groups work to make sense out of them through traditional scholarship, such as historians or digital humanities pedagogues. These scholars might approach R-Shief as a repository of data from social media on the “Arab Spring” and the Middle East region, overall, that offers the possibility of qualitative evidence. At the same time there are researchers, policy makers, businesswomen who could gain a competitive edge using a potential forecasting tool to read the global pulse of Twitter. The work has just begun. As I mentioned at the outset, in order to consider social media as a platform to forecast on the ground events, we must have a better understanding of the economics of social media. What is going on the ground throughout the Arab world is both unprecedented, and ultimately unpredictable. The reality is that R-Shief mediates between both worlds. Article and data visualizations by VJ Um Amel. Data mining by Ian Jones. This is an R-Shief Labs project. ---------------- 1. In response, a growing number of metaphors around virtual economies of time and value are rapidly emerging – such as attention economy, the distraction economy, the reputation economy, etc… -- building social capital through virtual identities. For example, Ian Bogost talks about membership (giving up data about yourself) versus licensed economies online. 2. Aristotle talks about art as mimesis and describes in great detail the mimetic act. So does that mean that work that is not mimetic, but about embodying, not considered as art by all? |

|

5846 views

|

| Thread Tools | Search this Thread |

| Display Modes | |

|

|